In honor of US National Sexual Assault Awareness Month, and for my 100th blog post, I wanted to cover a topic that is really important to me. This will be the first in my Let’s Talk About It series, looking at complicated or serious topics and exploring it in pieces a post at a time.

Today I want to talk about the neurobiology of trauma, specifically in regards to rape or sexual assault. This is a complic

ated topic that many others cover better than me so I’m going to do as much of an overview as I can, and because there’s a lot to cover I will only touch on pieces.

TRIGGER WARNING FOR ANYONE WHO HAS SURVIVED RAPE OR SEXUAL ASSAULT: I will be talking about what happens in

the body and brain during trauma, so it’s possible some wording might be triggering. This focuses on hormonal reactions and the chemistry of the brain. Please do not read further if you think this will be detrimental for you.

Regarding this post:

First, you might notice me switch between victim, survivor, and victim/survivor. There is no specific reason for where I use each. The term ‘survivor’ is what I’ve seen preferred by those who have survived assaults and they are part of my target audience; however, another large part of my target audience is people who have never experienced an assault and who do not understand why things happen the way they do, and oftentimes that demographic uses the term ‘victim.’

Second, you should know that there are a lot of misconceptions about rape and sexual assault, and this feeds into rape culture. Two main myths of rape/sexual assault can be explained by neurobiology and very human responses to trauma so those are the two I will cover in this post. There are a lot of other myths and misconceptions so if you are interested in me talking more about this topic, let me know.

-

MYTH NUMBER ONE: It isn’t rape if the person didn’t say no/fight back.

-

MYTH NUMBER TWO: If someone says they were raped but their story doesn’t make sense, it means they’re lying or covering something up.

Other myths that could be covered in more detail if anyone wants:

- If a person is raped when they are drugged or drunk it’s their fault and/or it isn’t actually rape (untrue; in many places you can’t legally consent if you’re under the influence of anything)

- People lie about being raped all the time (actually, only about 2-8% do, compared to 66% who don’t report to authorities for fear that they won’t be believed)

- You have to worry most about being raped by a stranger (not accurate; over 2/3 of rape or sexual assault is committed by someone the person knows)

- Men can’t be raped, especially by a woman, because men always want sex (this is a huge topic so in short, this myth is completely untrue and pisses me off every time I see it said or implied)

- Everyone is just as likely to be raped as anyone else (another huge topic, but: no. While some forms of sexual assault may have similar percentages for different demographics, there are some statistics and likelihood of vulnerability based on sexual orientation, gender identity, race, age, and more)

NEUROBIOLOGY AND TRAUMA

Myths #1 and #2 listed in red above can very easily be explained by the way the brain and body respond to trauma. Important facts to know right away that I will explain in detail beneath the cut:

- It isn’t fight or flight– it’s fight, flight, or freeze

- The hormones that are released at the time of trauma determine the response the victim/survivor will have, and the survivor has no control over this response

- Memories are recorded completely differently in traumatic situations vs normal situations

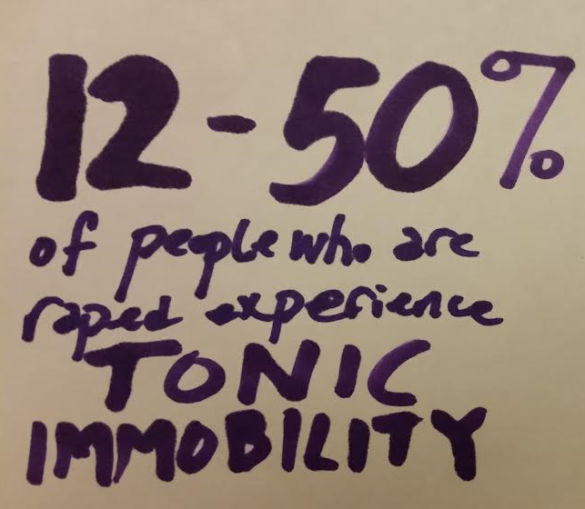

- A percentage of rape victims/survivors are literally paralyzed by their own body during the assault

Disclaimer: I gathered this information through research in multiple sources but especially from three nationally recognized subject matter experts. I listed their names, credentials, and links at the bottom of this post. I highly recommend you check them out if you find this topic interesting at all.

During a traumatic event, a few things happen:

- The brain recognizes something traumatic is happening and tries to compensate both in the mind and body

- The executive part of the brain that normally tells you, “This is logical, that is not” shuts down because it takes too long to make decisions, and the more “primitive” part of the brain that is all about instant reactions takes over

- The pituitary gland basically says, “Holy shit, this is bad, we need to deal with this right now” and tells the adrenal glands how to react

- The hormones that are released at the time affect the reactions the person has

- All this together means that the person may have their response dictated by the hormones their body releases, and their actions at the time or in retrospect may not seem to make any sense logically to others or, potentially, even themselves

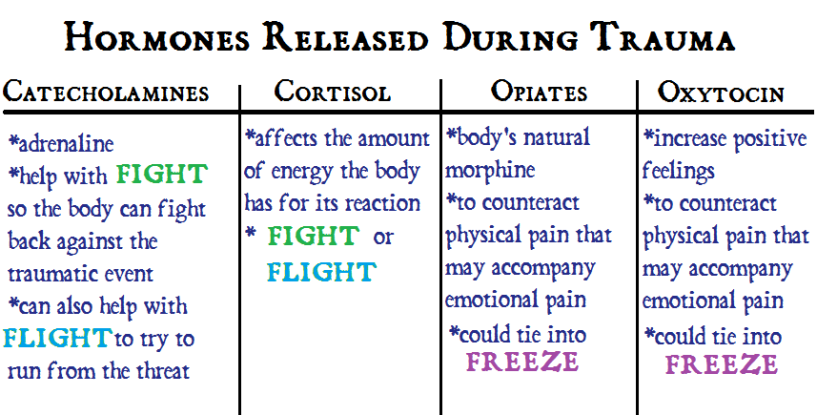

HORMONES AND TRAUMA

Here is an overview of hormones that are or can be released during a traumatic event:

If you ask most people, “What would you do if someone tried to rape you?” they’d probably say, “Oh, of course I would fight them off and scream for help.” But you don’t have the luxury of making those decisions in a traumatic event. Your body recognizes that something terrible is happening and it snaps over into automatic protection mode.

Depending on which hormones are released in which levels will affect the way you would respond immediately or afterward. One response I want to cover is related to cortisol, which as mentioned affects the amount of energy. Although I forgot to mark it on the above graph, cortisol can trigger the freeze response. Under the right circumstances, those hormonal influxes can trigger an entire shutdown of the body.

This is what’s known as “tonic immobility” or “rape-induced paralysis.” During tonic immobility, the body is literally paralyzed. And that is literally-literally, not figuratively-literally. You would not be able to speak, or move your head, or push anyone off, or call for help. You couldn’t tell someone no or stop. You couldn’t tell them anything.

Tonic immobility is not a super widely known phenomenon, so unfortunately a lot of people still believe that if someone doesn’t fight someone off tooth and nail that they aren’t really against what’s happening. But actually, if someone is paralyzed by terror that only gives even more credence to the fact that they didn’t want that to happen, and that they were so incredibly traumatized or afraid that their body’s only defense mechanism was to turn them to stone.

Tonic immobility is not something the person can choose to happen to them, or that they can affect once it occurs. They are caught in their own body and have to wait until the effects wear off naturally or somehow something else snaps them out of it. It is completely uncontrollable. Research suggests that survivors of previous sexual assault are slightly more likely to experience tonic immobility.

*****GANG RAPE TRIGGER WARNING FOR THIS PARAGRAPH ONLY!! ******

There are really sad stories involving tonic immobility, like of a young woman who was raped at a fraternity house and she was so shocked that she experienced tonic immobility without even understanding it was happening to her. The rapist saw that she wasn’t moving after he finished assaulting her, so he called all his friends in and they raped her one by one while she was unable to move. Her friend eventually realized what was happening and had to literally drag her off the bed and away, and later said she was like dead weight.

****END EXTRA TRIGGER WARNING****

Another very sad part of tonic immobility is that, because even a lot of survivors don’t realize it exists, there can be situations where a survivor might have experienced tonic immobility during their assault and later they thought back on it and judged themselves harshly or even hated or blamed themselves for not having fought back or said anything. They didn’t know that the paralysis had been a completely natural response by their body, that they couldn’t help it and it wasn’t their fault at all–any more than the rape was– and that it’s actually a very common reaction. So they assign even more blame to themselves that should never exist, and it adds to the trauma and weight of the memory rippling even farther out into their lives.

MEMORIES AND TRAUMA

image taken from http://uvamagazine.org/articles/memory/

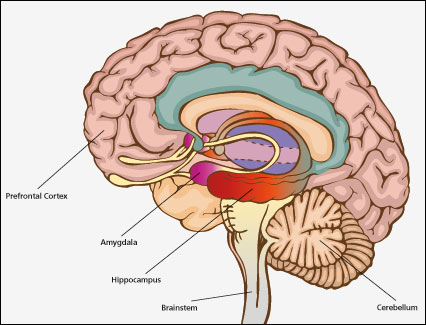

Below is an oversimplification of how the brain works in regards to memories and immediate reactions.

Prefrontal Cortex – the adult

I mentioned earlier the ‘executive’ part of the brain, which is the prefrontal cortex. Think of it like the leader of a committee, or the adult in your brain. It takes all the information your brain throws at it, parses through it and says, “Okay, this is what we’re going to do.” The prefrontal cortex helps stop impulsive, emotion-based responses. For example, “That sure is a pretty red berry…. but I remember that some berries are poisonous, so I’d better not eat that unless I know.” Or, “This guy is pissing me off… but since it’s my boss and I know I’m just having a bad day, I’d better stay quiet and not lash out or I could lose my job.”

Generally, the prefrontal cortex doesn’t stop fully forming until a person is around 25 so you can also think about all the bizarre or seemingly shortsighted or stupid things young people do, and imagine those being the things that the prefrontal cortex might otherwise prevent.

Amygdala – emotions and reactions

One of the oldest (evolutionarily speaking) and most primitive parts of the brain, think of this as pure emotional reaction. For example, you’re watching a TV show and a shark jumps at the screen; you jump or gasp even if you know it poses you absolutely no danger. One source I saw said that the amygdala also stores emotional memories.

Hippocampus – the librarian

I always like to imagine the hippocampus as a squirrel of a librarian, taking pieces of information and burying it here and there where it may or may not be properly recovered. That’s probably just my own incorrect mental image of it, but it’s how I like to think about it. The hippocampus is the part of the brain that processes information into memories. That same source also said it stores episodic and semantic memories.

Hormones and memory

Why does any of this matter? For two reasons.

- When experiencing a traumatic event, the body/brain realizes the prefrontal cortex is going to take way the hell too long to make an executive decision and that the person will be in danger during that time. So, the prefrontal cortex completely shuts down, and the amygdala takes over.

- The hippocampus and amygdala are really sensitive to hormonal fluctuation — and guess which hormones mess the most with them and their ability to record memories? The same four hormones I listed earlier that the glands dump out: catecholamines, cortisol, opiates and oxytocin.

What does all that gobbledygook mean? Four things that fall after one another like dominos:

- The person’s initial reaction to trauma is the fastest and most automatic reaction the body or brain can do to prevent further harm, without consulting the ‘logical’ part of the brain. Thus, their reactions might later “make no sense” to other people or even themselves, and at times can be completely counterintuitive.

- The way the body reacts to protect itself is also the most damaging to the parts of the brain that are in charge of recording everything

- Thus, their memories will be extremely emotional and episodic and will not follow the usual “first this, then that, who/what/where/why/when”

- Which means people think they’re lying when they later can’t answer even seemingly simple questions like, “Well, what did he look like?”

This also means that the victim/survivor is incapable of accessing the more “logical” options during an assault, let alone even begin to act on them.

Like tonic immobility, this is not something the victim/survivor chooses to happen or even something they have any amount of control over. It’s a totally normal mammalian response to fear or threat. Their body and brain are both on autopilot and those two functions are working against each other in the rush to protect their life.

Memories

Now, going back to memory. Think back to a totally normal day; something that was not traumatic. Can you remember the events that led up to it? Can you remember how it happened, in what order, and why? How you felt about it or what your senses told you at the time?

Here’s a memory I have:

I used to stay at the family farm during the summer. It was a dairy farm, among other things, so one of the barns was filled with cows, and you had to walk through a little room to get to them. That little room held a giant cylindrical, metal machine that droned deafeningly and refrigerated the milk. It was so loud that I heard it even inside the farmhouse with all the windows and doors shut, and when I was in the room it made me feel nauseated from the intensity. That room was tiny; barely bigger than the machine, and all up and down the walls were items I didn’t know the names or purposes of. Circling around the machine, I could reach the door into the main milking shed, with its skinny concrete strip down the center, the receptacles for manure, the spaces on either side for cows to be kept in place while they were milked, and the gate at the far end that let the cows out to pasture. Sometimes my cousins went out to that deafening machine to fill jugs with milk, and because it was pure milk it was really strong and sometimes had a film that floated to the top. Upstairs in the barn were haystacks, and a rope tied to a ceiling joint that we swung around on as kids, swooping over the gaps in the floor leading to the storey below; pretending we were Tarzan and Jane while hay pricked at our bare legs and we whooped loud enough to echo out through the open wooden shutters.

I can tell you all of that like a story because they are good memories for me; they are normal and not traumatic. If I think about it hard enough, I could probably tell you what happened before or after different events.

But when the amygdala is in control, it knows only emotional and sensory information. When the hippocampus tries to record the information but is compromised by hormonal releases, the emotions and senses are scattered all around and turned into disconnected flashes. Like someone took pieces of a disconnected story, ripped the paper apart, tossed the pieces into the wind in handfuls in different directions at different times, where it was thrown all around and scattered across miles, and then later they were asked to gather all the pieces and put it together into a coherent and chronological story.

Even the pieces that can be reassembled will still be stained with the intensity of the emotions so even thinking of them can be traumatizing. The information will come slowly over time as the brain tries to make sense of the experience but some things were just not recorded at all in the first place so can’t be recovered, or may be more difficult to recover, because it was the amygdala in charge at the time and it didn’t care about telling a story about it later; it cared about staying alive.

Experts recommend that victims of traumatic events aren’t interviewed until three sleep cycles have passed, as that will give more time for some of the information to fall into place and make a little more “sense.”

But can you really understand properly what I’m talking about above? Maybe you can. But since I’m a visual person, I think visuals help.

Let’s go back to my memory of summer on the farm, and that milking shed. And then let me also tell you that one day when I was maybe four or five, something happened that scared me so much that I wouldn’t go back into that shed for a long time, and for years afterward I was scared of cows.

Here’s what my normal memory would look like visually:

Now, what story am I telling you about that day that had such an impact on me when I was young?

Is it any clearer like this?

Or this?

Even like this, can you piece together the story?

Think of that like the way memories are recorded, stored, and gathered again between a non-traumatic and traumatic event. If it helps, you could even imagine the above progression of pictures as the way memories are crowded against each other right after the event, and the slow unfolding of them into something more cohesive over the following days/time period until it orders into something with more easily followable connections.

But even then, as you can see in the last picture, it’s all about disconnected pieces, emotions, and flashes. Using my memory for a visual, it’s about sensory information like the sunlight and warmth and the blue sky, combined with the emotional reactions of fear and wanting to flee and being stuck.

I want to be very clear that I am of course in no way trying to equate a memory of when I was scared and almost accidentally hurt by cows on the farm as a child, with the trauma experienced by a person who was sexually assaulted or raped. I use that memory of mine merely as a visual example to show how even on much smaller events, which might make a person develop aversions or fears of seemingly benign or normal things (like cows), there is still a shift in the way the memory is recorded and recovered years later.

Memory is something that’s a very large topic even on its own, because for many years it was assumed that memory was something static; that once you experienced it and recorded it in your brain, it was always there in that exact same form and any embellishments that appeared over time were merely a result of the details becoming fuzzier as the brain weakened with age. But more recent research suggests that memories are much more dynamic and elastic; that every time we access them we are actually rewriting them, and that this is part of the reason why stories people tell may change over time. That it isn’t just the fuzziness of age, but that the memory itself may be changing the more we remember it.

That would be a whole other topic in and of itself.

For now, I hope this (admittedly, still long) overview of the neurobiology of trauma in regards to sexual assault/rape helped to show you how and why the way people react to trauma may not be what you would assume would happen, and why you should always believe someone if they tell you they were raped or sexually assaulted. Because only about 2-8% of the time do people lie about having been raped or sexually assaulted, but much more often (66% of the time) do people not report it to authorities or–and I have no statistics on this–even to friends or loved ones. This is for many reasons but one large reason that comes up is they fear they won’t be believed.

There is a frustratingly pervasive stigma set on victims/survivors of sexual assault and rape… a fear on behalf of the person who experienced it that they won’t be believed, that they’ll be blamed or questioned; that somehow others will think or say that it was their fault. Meanwhile, statistics show a disturbingly low chance of the rapist being caught, tried, convicted, and see any punitive actions such as jail or prison time as a result.

I read somewhere that it’s thought that on average a rapist commits 6 rapes, which means if they aren’t caught after the first one there are probably very likely to be 5 more victims of that rapist’s actions. 6 people whose lives will change dramatically after the assault; who have to live with the memory of it every day of their lives, whose entire existence might shift in response, and who might suffer long-lasting psychological consequences like complex trauma, PTSD, depression, suicidal tendencies, or more.

RESOURCES AND WHAT TO DO

There is a lot of work that needs to be done on the topic of rape and sexual assault, to protect survivors and provide them as many resources as possible, while also finding better ways to help prevent the assaults from happening in the first place.

And let’s be clear on that: prevention is NOT on the hands of the survivor! If someone is raped or sexually assaulted, it isn’t because they didn’t do something right. It isn’t their fault. It isn’t a result of their actions.

Rape happens because the rapist raped someone. The way to prevent rape is to stop people from raping others. It isn’t to tell all the potential victims/survivors of the world how to avoid someone else committing a crime against them. It’s to tell all the potential rapists/assaulters of the world not to commit that crime.

But you also have to remember that rapists are not inhuman monsters. That’s something very important to keep in mind, because the tendency to turn them into the “other” means that people don’t recognize red flags in the people surrounding them. This isn’t saying it’s okay or excusable IN ANY WAY for someone to rape someone else; rather, it’s to say that imagining them to be something other than human doesn’t help the international discourse on this topic, which also means it doesn’t help hold the rapists accountable for their actions. If people think only a truly evil, monstrous individual could rape someone else, then they won’t blame the person who actually did it if they have had more nuanced interactions with them.

There’s also a lot to do with how people phrase the idea of rape. For example, using the word ‘rape’ might mean that some people do not self-identify as having been raped or having raped someone else, but using terminology like “forceful sexual intercourse” means they do self-identify with it. And then you can also get into the massive topics of how men are raised and treated in the US, at least, as well as misogyny and its affect or relation to media and the oversexualization of women, and the effects of gender roles, and how all of this plays into not only rape culture but also the fears survivors have of how people will react if they say they were raped–and the reality for many survivors of people reacting exactly that way.

But that, again, is a whole other topic, as is all the things that can expand out from this like human/sex trafficking, and the recent shift in a paradigm of looking at prostitution not as a victimless crime or something where the ‘sex worker’ or ‘prostitute’ is willingly involved in the situation, but rather many times is a consequence of other previous events or is, itself, human trafficking.

All of this is very interconnected, in my opinion, and so it’s something that will take a lot of effort and time to address. But the good news is that there are some very simple steps everyone can take that will go a very long way toward that goal:

- If someone tells you they were raped or sexually assaulted, believe them. Support them.

- If you were raped or sexually assaulted, seek professional help so you can have the support you need

- Research the information out there to get a better understanding of what happens, why, and how to help

- Call people out on playing into rape culture or otherwise counteract rape culture however you feel comfortable

- Be a good bystander

- Be a good friend or loved one

There are many, many organizations out there that focus on rape and sexual assault, so I won’t even attempt to list them all. Additionally, I am unfamiliar with the specific resources internationally or locally where you may be. But know that at least in the United States, there are many victim advocacy groups out there who can help you through the system if you have been assaulted, and if you have not been assaulted but want to learn more to help people who have those groups can also provide you resources to better understand, or may provide volunteer opportunities for you to get more involved.

So here are only a few of the various organizations out there you could check into, in no particular order:

- NSVRC/National Sexual Violence Resource Center: — this also has a list of organizations by state

- Brave Miss World; this is a documentary and also an organization created by the woman who is the focus of the documentary. I recommend you watch it if you want more information but if you have been raped or sexually assaulted, it might be triggering for you so take caution. ((For people interested in information on rape culture, another very good documentary on a real life tragedy is India’s Daughter, but it’s also extremely sad and AGAIN I caution a trigger warning to any survivors))

- Project Unbreakable; a tumblr photography project that is aimed at giving a voice to survivors

- 1in6; resources for male survivors of childhood sexual abuse

- RAINN/Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network; the US’s largest anti-sexual assault organization

- Force: Upsetting Rape Culture; in their words: a creative activist collaboration to upset the culture of rape and promote a culture of consent

As I said, that is only a small snapshot of the groups out there.

If you need immediate help:

- RAINN crisis line: 1 800 656 HOPE (4673)

- 1in6 24/7 online chat support, and counseling: https://1in6.org/men/get-help/online-support-center/

Check local organizations for other crisis lines.

MORE INFORMATION/SOURCES

I am not the one who discovered any of this neurobiological information, and I am by no means an expert on neurobiology. I only know what I’ve read and researched and watched; what information I took away from that and how I ordered it in my head. I could have misrepresented small details of this information here or there on accident.

If you are interested in this topic and want to learn more about it, I highly recommend you go directly to the source. Check out the nationally recognized subject matter experts on neurobiology and its relation to sexual assault/rape and trauma:

Dr. Rebecca Campbell, Ph.D. Professor of Community Psychology and Program Evaluation at Michigan State University. She focuses especially on violence against women and how the legal/mental/medical systems respond to the needs of rape survivors. As well as giving presentations on the neurobiology of sexual assault across the nation to many fields, from college campuses to medical professionals to law enforcement, she also works with Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE) to develop intervention programs to provide comprehensive post-assault services to survivors.

Russell Strand, retired U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Division special agent and currently Chief of the Behavioral Sciences Education & Training Division at the U.S. Army Military Police School. He is especially known for having developed FETI/Forensic Experiential Trauma Interviews; a system for military/law enforcement to reevaluate the way they conduct interviews of trauma survivors. With his military background, he excels at putting information in a way that law enforcement professionals can understand.

David Lisak, Ph.D. Clinical psychologist, forensic consultant, professional trainer, and public speaker. One focus of his work is non-stranger rape, which has helped guide rape prevention and response policies in major institutions, including the US Army and universities. He’s also done research on male survivors of childhood sexual abuse and is a founding board member of 1in6, a non-profit devoted to helping men who were sexually abused as children.

—

A lot of the information in this post came especially from from Professor Campbell, who I find does an excellent job of parsing complicated research into easily understandable explanations. I haven’t had the opportunity to watch as many presentations from the other two yet. But now that you can see their specialties, hopefully you can identify which of them you want to look into first. They are all nationally renowned professionals on this topic, which is why in this case I didn’t cite sources throughout this post. Since the information I have comes mostly from these three, all you have to do is start looking into the information they’ve put out and you’ll see even better context of the pieces I drew out and focused on for this.

Thank you for reading this far into the post and for joining me on my first Let’s Talk About It post. I hope it was interesting or helpful in some small way, at the very least in bringing your attention to any of the sources or resources so you can find more of what these dedicated professionals are doing and how you can aid them in their effort.

No matter your reason for being at this post, no matter your current or past circumstances, I’m wishing you all the very best, and as much hope and comfort and support as you can have in your life. Please never forget that you’re important and beautiful and special, and those facts never change no matter what darkness other people might have tried to pull into your light. And if you’ve had no darkness turned on you, then I hope you can be a light that shines for the people who are caught in the shadows, straining to break free.

Brightest of blessings to you and yours.

-Ais

I really wanted to thank you for this post. My therapist just started telling me about freeze response yesterday and it’s the first time I’ve really heard of it. This has really helped make sense of it and I think start thinking about the idea that the reaction I had was out of my control, and that I wasn’t compliant.

Thanks again.

Oh good! I’m so glad first of all you’re seeing a therapist and also that your therapist mentioned it! I don’t know why it isn’t more well known but it really needs to be, so people know exactly what you said: that they, and you, are not compliant if that is what happened. That automatic reaction of the body is 100% not your fault. In not quite the same but similar terms, that would be like blaming oneself for blinking or breathing. It’s the way our body keeps us alive; it’s just that in a traumatic event the body makes different decisions than in non-traumatic situations. I’m really glad this was able to help make sense of it in any way for you, especially for something as complicated and traumatic as this topic. I’m wishing you all the very best–what you deserve is that and nothing less. I hope as you have more time to look into tonic immobility, you’ll have more time to reevaluate your own circumstances and maybe be able to relieve yourself of a little bit of the burden you may have had when you didn’t know tonic immobility existed, and when you may have mistakenly believed you were at fault in any way. Please be well, my friend. And please also be as understanding of and kind to yourself as possible. That, too, is something you deserve, and nothing less.

So are you saying that the memory of a rape or a potential rape is stored in the Amygdala or the Hippocampus? I am not sure I totally understand, thanks by the way for the excellent information.

My understanding is that they are essentially stored similarly but recorded differently, but I’m not 100% sure on that aspect of it. You would definitely want to verify with neurobiologists or updated research on the topic to make sure I’m not leading you wrong accidentally through a misunderstanding of the materials I read a few years ago 🙂 Thank you and I hope you have a good day!